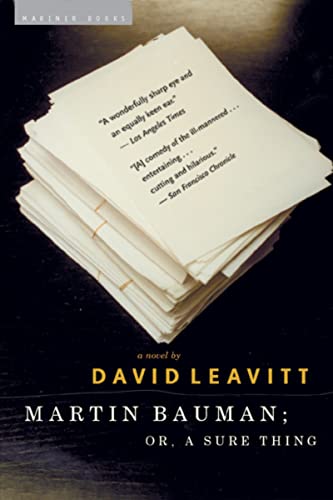

Items related to Martin Bauman: or, A Sure Thing

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

I first met Stanley Flint in the winter of 1980, when I was nineteen.

He was between editorial greatnesses then, just fired by the famous

magazine but not yet hired by the famous publisher. To earn his keep

he traveled from university to university, offering his famous

Seminar on the Writing of Fiction, which took place one night a week

and lasted for four hours. Wild rumors circulated about this seminar.

It was said that at the beginning of the term he made his students

write down their deepest, darkest, dirtiest secrets and then read

them aloud one by one. It was said that he asked if they would be

willing to give up a limb in order to write a line as good as the

opening of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It was said that

he carried a pistol and shot it off every time a student read what he

considered to be a formidable sentence.

As the former fiction editor of Broadway magazine, Flint was

already notorious in those days, though his notoriety was of an oddly

secondary variety, the result of his having published, during his

tenure there, the first stories of some writers who had gone on to

become great - so great, in fact, that their blazing aureoles shone

backwards, as it were, illuminating the face of Flint the Discoverer,

Flint the Seer, who had had the acumen not only to recognize genius

in its rawest form, but to pluck it from the heap, nurture it, refine

it. Soon he had such a reputation that it was claimed he needed only

to make a phone call and a writer would have a publishing contract,

just like that - until the editor in chief of Broadway, either from

jealousy or because Flint had had an affair with his secretary (it

depended who you asked), fired him. Much media uproar followed but no

job offers, and Flint went to work as a teacher, in which role he

cultivated an aura of mystic authority; for instance, he was supposed

to have gotten one of his students a six-figure advance on the basis

of a single paragraph, which was probably the real reason why three

hundred people had applied for the fifteen places in his class.

I remember vividly the room in which that seminar took place.

Located just off the informal library of one of the dormitories, it

was oblong and narrow, with wheezing radiators and shelves full of

books too obscure or valueless even to bother cataloguing. On the

chalkboard - left over from an Italian class that had met earlier in

the day - the conjugation of the verb mangiare was written in a tidy

hand. Because I had arrived twenty minutes early the first evening,

only one other person was seated at the battered oak table, a girl

with circular glasses and tight blond braids, her attention

scowlingly focused on some German worksheets. Not wanting to appear

idle in the presence of such industry, I busied myself arranging my

coat and scarves over the back of a chair (it was January), then,

pulling a book at random from one of the shelves, sat down and

started to read it. The book was called Dawn to Sunset, and it had

been published in 1904. On the title page its author had written the

following inscription: "Con molto affetto, from one who spent his

formative years "neath thy Ivied walls, James Egbert Hillman, "89.

Sorrento."

"Florence!" the first chapter began.

Flinging open the curtains, Dick Dandridge stared wonderingly at the

piazza in morning light. Such a buzz of activity! It was market day,

and at little stalls old women in black dresses were selling apples

and potatoes. Two horses with caps on their ears pulled a wine cart

past the picturesque medieval church. Italy, Dick thought,

remembering, for a moment, his mother weeping as his ship set sail

from New York, and then his adventures in London, in Paris, at the

customs house in Chiasso. He could not wait to get out into it, and

pulling his nightshirt over his head, he called out to his friend

Thornley, "Get up, slug-a-bed! We"ve Florence to see!"

A Hispanic girl with bangs and acne on her forehead now came

in and took a seat; then a pair of boys, in avid conversation; then a

boy with a withered arm whom I recognized from a class on modern

poetry the semester before. We saluted each other vaguely. The girl

with the braids and the big glasses put away her worksheets.

A conversation started. Over the voices of Dick Dandridge and

his friend Thornley, one of the pair of boys said, "I wasn"t on the

list, but I"m hoping he"ll let me in anyway." (At this last remark I

smiled privately. Though only a sophomore, I was on the list.) The

boy who had said this, I observed, was handsome, older than I, with

wire-rimmed spectacles and a two-days" growth of beard; it pleased me

to think that Stanley Flint had preferred my submission to his. And

meanwhile every seat but one had been taken; students were sitting on

the floor, sitting on their backpacks, leaning against the shelves.

Then Stanley Flint himself strode through the door, and all

conversation ceased. There was no mistaking him. Tall and limping,

with wild dark hair and a careful, gray-edged beard, he carried a

whiff of New York into the room, a scent of steam rising through

subway grates which made me shudder with longing. Bearing a wine-

colored leather briefcase with brass locks, dressed in a gray suit,

striped tie, and fawn trench coat that, as he sat down, he took off

and flung dramatically over the back of his chair, he seemed the

embodiment of all things remote and glamorous, an urban adulthood to

which I aspired but had not the slightest idea how to reach. Even his

polished cane, even his limp - like everything about Flint, its

origins were a source of speculation and wild stories - spoke to me

of worldliness and glamour and the illicit.

He did not greet us. Instead, opening his briefcase, he took

out a yellow legal pad, a red pencil, and a copy of the list of

students he had accepted for the seminar. "Which one of you is

Lopez?" he asked, scanning the list. "You?" (He was looking at the

girl with bangs and bad skin.)

"No, I"m Joyce Mittman," the girl said.

"Then you must be Lopez." (This time he addressed her

neighbor, another Hispanic girl, her hair cut short like a swimmer"s.)

"No, I"m Acosta," the neighbor said.

A low murmur of laughter now circulated - one in which

Flint"s raspy baritone did not take part. Looking up, he settled his

gaze on a tall, elegant young woman in a cowl-neck sweater who was

standing in the corner. She was the only other Hispanic in the room.

"Then you must be Lopez," he said triumphantly.

The girl did not smile. "Did you get my note?" she asked.

"Did you bring the story?" he answered.

She nodded.

"Over here, over here." Flint tapped the table.

Extracting some pages from her backpack, Lopez walked to the

front of the room and handed them over. Flint put on a pair of

tortoiseshell half-glasses. He read.

After less than half a minute, he put the pages down.

"No, no, I"m sorry," he said, giving them back to her. "This

is crap. You will never be a writer. Please leave."

"But you"ve only -"

"Please leave."

Lopez wheezed. A sort of rictus seemed to have seized her -

and not only her, but me, the other students, the room itself. In the

high tension of the moment, no one moved or made a sound, except for

Flint, who scribbled blithely on his legal pad. "Is something wrong?"

he asked.

The question broke the spell, unpalsied poor Lopez, who

stuffed the crumpled pages into her backpack and made for the door,

slamming it behind her as she went.

"In case you were wondering what happened," Flint said,

continuing to scribble, "Miss Lopez sent me a note requesting that I

look at her story tonight, as she had missed the submission deadline.

I agreed to do so. Unfortunately I did not think the story to be

worthy." Gazing up from his pad, he counted with his index

finger. "And now I see that there are twenty - twenty-two people in

this room. As I recall I selected only fifteen students for the

class. I would appreciate it if those of you whose names were not on

the list would please leave now, quietly, and without creating a

spectacle of the sort that we have just witnessed from Miss Lopez."

Several people bolted. Again Flint counted. Nineteen of us

remained.

"I should tell you now," Flint said, "that the stories you

submitted, to a one, were shit, though those written by the fifteen

of you whom I selected at least showed conviction - a wisp of truth

here or there. As for the rest, you are courageous to have stuck it

out, I"ll give you that, and as courage is the one virtue every

fiction writer must possess in spades, I shall let you stay - that

is, if you still feel inclined after I tell you what I expect of you."

Then he stood and began to speak. He spoke for two hours.

So began life with Stanley Flint. I"m sorry to say I don"t

remember much of what he said that evening, though I do retain a

general impression of being stirred, even awed; he was a marvelous

raconteur, and could keep us rapt all evening with his monologues,

which often ranged far afield from the topic at hand. Indeed, today I

regret that unlike the girl with the braids - her name, I soon

learned, was Baylor - I never took notes during class. Otherwise I"d

have before me a detailed record of what Flint had to tell us those

nights, rather than merely the memory of a vague effulgence out of

the haze of which an aphorism occasionally emerges, fresh and entire.

For instance: "The greatest sin you can commit as a writer is to put

yourself in a position of moral superiority to your characters."

(Though I have never ceased to trumpet this rule, I have often broken

it.) Or: "People forgive genius everything except success."

Or: "Remember that when you ask someone to read a story you"ve

written, you"re asking that person to give you a piece of his life.

Minutes - hours - of his life." (The gist of this idea was expressed

by "Flint"s first principle," of which Flint"s first principle was

exemplary: "Get on with it!")

It was all a great change from the only other writing class

I"d ever taken, a summer poetry workshop sponsored by the Seattle

junior college - a remnant of sixties idealism, all pine trees and

octagons - where my mother had once gone to hear lectures on Proust.

Of this workshop (the word in itself is revealing) I was the only

male member. Our teacher, a young woman whose watery blond hair

reached nearly to her knees, imparted to the proceedings the mildewy

perfume of group therapy, at once confessional and pious. Often class

was held outdoors, on a lawn spattered with pine needles, which is

perhaps why my memory has subsequently condensed that entire series

of afternoons into the singular image of one of my classmates, a

heavy girl with red spectacle-welts on her nose, standing before us

in the sunlight and reading a poem of which only one line -"the

yellow flows from me, a river"- remains, the words themselves flowing

from her sad mouth in a repetitive drone, like a river without source

or end.

Flint"s seminar, to say the least, had a different rhythm. It

worked like this: at the beginning of each session a student would be

asked to read aloud from his or her work. The student would then read

one sentence. If Flint liked the sentence, the student would be

allowed to continue; if he did not, however - and this was much more

common - the student would be cut off, shut up, sent to the corner. A

torrent of eloquence would follow, the ineffectuality of this slight

undergraduate effort providing an occasion for Flint to hold forth

dazzlingly, and about anything at all. His most common complaint was

that the sentence amounted to "baby talk" or "throat-clearing"- this

latter accusation almost invariably followed by the

invocation "Remember Flint"s first principle!" and from us, the

responsorial chant, "Get on with it!"

Soon we understood that Flint loathed "boyfriend stories,"

stories in which the protagonist was a writer, stories set in

restaurants or cocktail lounges. To cocktail lounges he showed a

particular aversion: any story set in a cocktail lounge would provoke

from him a wail of lamentation, delivered in a voice both stentorian

and grave, a sermon-izer"s voice, for the truth was, there was

something deeply ministerial about Flint. Meanwhile the student whose

timid words had provoked this outpouring would have no choice but to

sit and percolate, humiliated, occasionally letting out little gasps

of self-defense, which Flint would immediately quash. An atmosphere

of hyperventilation ensued. The windows steamed. Those Flint had

maligned stared at him, choking on the sentences in which, a moment

earlier, they had taken such pride, and which he was now shoving back

down their throats.

Yet when, on occasion, he did like a sentence - or even more

rarely, when he allowed a student to move from the first sentence to

the second, or from the second to the third - it was as if a window

had been thrown open, admitting a breath of air into the churning

humidity of that room, and yet a breath that would cool the face of

the chosen student only, bathing him or her in the delightful breeze

of laudation, while outside its influence the rest of us sweltered,

wiping our noses, mopping our brows. Sometimes he even let his

favorites - of whom Baylor, the girl with the braids, soon became the

exemplar - read a story all the way to the end. On these occasions

the extravagance of Flint"s praise more than matched the barbarity of

his deprecation. Not content merely to pay homage, he would seem

actually to bow down before the author, assuming the humble posture

of a supplicant. "I"m honored," he"d say, "I"m moved," while the

student in question glanced away, embarrassed. We all knew that his

adulation, at such moments, was over the top - a reflection, perhaps,

of the depth to which his passions ran, or else part of a strategy

intended to make us feel as if his approval were something on which

our very lives depended.

Still, he was nothing if not consistent. Whether delivering

tirade or paean, he never wavered from his literary ethos, at the

core of which lay the belief that all human experiences, no matter

how different they might seem on the surface, shared a common

grounding. This theme ("Flint"s second principle") he trumpeted at

every opportunity. To perceive something one had gone through as

particular or special, he kept telling us, was to commit not merely

an error, but a sin against art. On the other hand, by admitting the

commonality that binds us all, not only might we win from readers the

precious tremor of empathy that precedes faith, we might also near,

as we could from no other direction, that mercurial yet unwavering

goal: the truth.

In retrospect, I wonder at my ability not only to survive,

but to thrive under such circumstances. Twenty years later I"m more

sensitive rather than less, more cowardly, less likely to consider

the ordeal of Flint"s criticism worth enduring. I feel sympathetic

toward poor Lopez in a way that I didn"t then. Also, so many people

have studied with Flint since 1980 that by now his detractors far ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherMariner Books

- Publication date2001

- ISBN 10 0618154515

- ISBN 13 9780618154517

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages400

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Martin Bauman: or, A Sure Thing

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.9. Seller Inventory # 0618154515-2-1

Martin Bauman: or, A Sure Thing

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.9. Seller Inventory # 353-0618154515-new

Martin Bauman; Or, a Sure Thing (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. Martin Bauman; Or, a Sure Thing 1.32. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780618154517

Martin Bauman: or, A Sure Thing by Leavitt, David [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. This item is printed on demand. Seller Inventory # 9780618154517

Martin Bauman: or, A Sure Thing

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABLIING23Feb2416190080035

Martin Bauman: or, A Sure Thing

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780618154517

Martin Bauman: or, A Sure Thing

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. 0th Edition. Special order direct from the distributor. Seller Inventory # ING9780618154517

Martin Bauman Or, a Sure Thing

Print on DemandBook Description PAP. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. THIS BOOK IS PRINTED ON DEMAND. Established seller since 2000. Seller Inventory # IQ-9780618154517

Martin Bauman; Or, a Sure Thing

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. 388 pages. 8.75x5.75x1.25 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # x-0618154515

Martin Bauman: Or, a Sure Thing

Book Description Paperback / softback. Condition: New. This item is printed on demand. New copy - Usually dispatched within 5-9 working days. Seller Inventory # C9780618154517