Items related to The Dream Of Spaceflight Essays On The Near Edge Of...

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Wyn Wachhorst

1. Why did you decide to start writing these essays? Has space exploration been a lifelong interest?

A. I grew up in the late forties and early fifties at a time when the fantasy of spaceflight and the promise of reality seemed almost in balance. I could carve balsa copies of the silver rocket from Destination Moon, inserting CO2 capsules that sent them hissing in cartwheels over the neighbor's fence, and have the exhilarating sense that I stood very near the leading edge. When I was twelve I read every book on spaceflight-all four of them. So I suppose it was inevitable that I would eventually write something on the subject once my life settled down-around age 60. I think the actual catalyst was a film called For All Mankind, released for the twentieth anniversary of the moon landing. It was my latter-day Destination Moon.

2. The space program has seen a lot of failures: the Challenger explosion, the flaws in the Hubble Space Telescope, the nightmares aboard Mir, the failure of two Mars missions. And many people say that even if unmanned space probes are justified scientifically, sending humans into space is a pointless extravagance. How do you answer these objections? What's the mission that justifies the danger and expense?

A: With regard to failure, it's easy to see the glass as half empty. To see it half full is to wonder at the fact that in almost twenty years only one shuttle was lost, that no one perished on Mir, that astronauts were able to repair the Hubble in space, and that most missions are enormously successful-sampling the soil of Mars, mapping the surface of Venus, revealing the volcanoes of Io and the ice seas of Europa.

But in the end, it's humans who must go into space. The usual rationales are certainly true: Humans have the awareness and flexibility required to face the unknown; they are far better than machines at solving problems and finding what they are looking for. Human settlements in space will end our confinement to one vulnerable world and provide the kind of isolation and freedom necessary to repeat the New World experience and create totally new societies and cultures. But Buzz Aldrin was more to the point when he noted that if you send a robot with a camera to Paris and peruse the pictures at home, you haven't really done Paris. Risk has always been the price of any successful venture, whether it be our migration out of Africa into the northern ice, the discovery of the New World, the shaping of a continent, or the preservation of that new freedom. There can be no success without the opportunity to fail.

The dream of the risk-free society must always reduce to the dream of animal comfort. The mission now, as always, is to pursue those qualities that differentiate us from the lower animals. To gaze into the night sky and feel the vastness and passion of creation is to glimpse an equally vast interior. We are aware of the stars only because we have evolved a corresponding inner space. Like Columbus, we enter space seeking the East in the west, journeying, as Joseph Campbell said, "outward into ourselves." We are a curious, wondering, self-reflective species, longing to complete some grand internal model of reality, to find the center by completing the edge.

3. At one point you suggest that exploration is an attempt to complete a grand internal model of reality, and at another that exploration is the driving force of evolution. Is there some relation between these two notions?

A. The urge to explore, the quest of the part for the whole, has been the primary force in evolution since the first water creatures began to reconnoiter the land. Living systems reach out to their environment, merging with larger systems in the fight against entropy. We know from the new science of chaos and complexity that an open system "perturbed" at its frontier may restructure itself, escaping into higher order. It is at its frontiers that a species experiences the most perturbing stress. The need to see the larger reality-from the mountaintop, the moon, or the Archimedean points of science-is the basic imperative of consciousness, the hallmark of our species. Living systems cannot remain static; they evolve or decline. They explore or expire. The inner experience of this imperative is curiosity and awe. The sense of wonder-the need to find our place in the whole-is not only the genesis of personal growth but the very mechanism of evolution, driving us to become more than we are. Exploration, evolution, and self-transcendence, and I should add the spirit of play, are but different perspectives on the same process.

4. Why the spirit of play?

A. The image of man on the moon that will endure is not the flag or the science but humans at play-the boyish exuberance, the pratfalls and belly flops, Gene Cernan bursting into song as he bounced like a rabbit with his basket of rocks down the Valley of Taurus Littrow, Al Shepard teeing off on Fra Mauro, Duke and Young yahooing as they bounded over the undulating plain in their moon jeep like lunar Keystone Kops. The frontier, like the world of the child, is a place of wonder explored in the act of play. Work is self-maintenance; play is self-transcendence, probing the larger context, seeking the higher order. Joseph Campbell has observed that in countless myths from all parts of the world the quest for fire occurred not because anyone knew what the practical uses of fire would be, but because it was fascinating. Those same myths credit the capture of fire with setting man apart from the beasts, probably because it was the earliest sign of that willingness to pursue fascination at great risk that has been the signature of our species. Robinson Jeffers once said that we require these fascinations as visions that "fool us out of our limits."

Beyond all the pragmatic apologetics, there is a certain unlikelihood about the Egyptian pyramid, the Gothic cathedral, or the Saturn 5 rocket; a towering, unearthly presence on the Libyan desert, the Florida coast, or the wheatlands of southern France. Like all final concerns, these great collective projects didn't arise from the ethic of work but in the spirit of play. Their great strength and beauty lay in their utter impracticality. It is difficult enough for Americans, whose values and traditions are rooted so deeply in the work ethic, to conceive of an imprudent project at the center of any life, let alone at the core of an entire culture. But the Protestant ethic itself may be the greatest collective project of all. Ironically, the pursuit of means as ends in themselves-equating wealth with happiness, power with success, isolation with freedom, change with progress-spawned the technological pyramid that has freed the mass of humanity from mere utility. Daniel Boorstin has suggested that we are no longer merely Homo sapiens but rather Homo ludens, "at play in the fields of the stars." We stand alone on the leading edge of evolution, exploring our horizons as children probe the world in play.

5. What do you mean by "the withered capacity for wonder that afflicts the postmodern mind"? Why do you say it's withered, and how will spaceflight help?

A. There is a failure of nerve in postmodern society, an ingrown homogenization similar to that of sixteenth-century Europe on the eve of New World expansion. There's a loss of vigor, an unwillingness to take risks, a spreading irrationalism, increasing bureaucratization, and an impotence of political institutions to carry off great projects. Cultural diversity declines while popular culture grows increasingly banal. The promise of space resembles the legacy of the Renaissance in that it offers not only rich new veins of empirical knowledge but a deprovincialization of the spirit. In a competitive society, pressured by uncertainties of status and self-esteem, people develop a buffering ego that protects them from debilitating anxiety, but also from creativity and discovery. Fearing loss of control, they revert to rigid, clear-cut, conventional thinking, adopting one shallow nostrum, one fashionable idea after another. A false self projects its own system of categories and expectations onto the world, recognizing only those things that can be quickly labeled and filed away in some well-worn category. What is eclipsed is the larger unconscious self-that part of the mind, grounded in feeling, that gives meaning to experience. Chronic stress has caused modern culture to lose sight of this mode, to view it as a threat to reason and control. The result is a withered capacity for curiosity and wonder.

Spaceflight will revitalize humanity and rekindle the sense of wonder. We are alive at the dawn of a new Renaissance, a moment much like the morning of the modern age, when most of the globe lay deep in mystery and tall masts pierced the skies of burgeoning ports, luring those of imagination to seek their own destiny, to challenge the very foundations of man and nature, heaven and Earth. It is no coincidence that literary golden ages coincide with peaks of frontier expansion, spawning a Homer, Shakespeare, Melville, Conrad, or Twain, while the closing begets Tennessee Williams and Jack Kerouac. The proverb of Solomon is more concise: "Where there is no vision the people perish."

6. How can schools help instill or restore a sense of wonder, especially with regard to science?

A. If science teaching were to begin with the great mysteries-things strange beyond comprehension, immensities beyond imagination-and work backward to the familiar, more students might become inspired. Surveys suggest that 80 to 95 percent of Americans are scientifically illiterate. Something like half of American adults do not know that the Earth goes around the Sun and takes a year to do it. Recent tests ranked American high school students 11th out of 13 nations in math and science. It seems ironic that at the very time when an explosion of knowledge has increased the scale and complexity of the cosmos a millionfold, so many of the young live jaded, geocentric lives. A major defect in science teaching is the focus on factoids, most of which are forgotten in adulthood. Rather than presenting the packaged load that is characteristic of virtually all introductory courses, we need to teach what science is about-the larger concepts, the method, the history, the wonder-the mysterious and awe-inspiring phenomena that will sustain interest in science long after the minutiae are forgotten.

At the core of both science and religion is a longing for the whole over the part, the why over the how. It is a search for roots, for something fixed and eternal. It is the hope that we are more than chance anomalies, that our essence somehow reflects that of the cosmos, that it is not a house but a home. What textbooks fail to consider, and few teachers are prepared to confess is that science, like religion, is most basically a quest for creation myths, stories that give our lives meaning.

There's a spiritual depth in millions of people, a space altogether neglected in school, that must be touched and tapped if we're to survive our own cleverness. Science is not a perfectible task, it's a continuing spiritual encounter with the mystery of being. In a world in which people write thousands of books and one million scientific papers a year, the literate layman is the one who can play with all that information and hear a music inside the noise. If we could teach that music, science would no longer languish in our schools and the will to explore would survive the likes of Senator Proxmire who, in nixing SETI [Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence], gave it his "Golden Fleece" Award.

7. You use the word "transformation" a lot. How is the rise of spaceflight symbolic of a transformation of Western culture?

A. The adolescence of humanity began with the age of exploration. The five-century campaign to subdue nature resembles the adolescent obsession with self-assertive power and is archetypally masculine. The attempt to tear ourselves from the planet, to become independent of Mother Earth, is the logical extreme-the last great Faustian act. The famous image of Ed White, drifting alone over the blue Pacific on America's first spacewalk-tumbling slowly in the windless, odorless void, hearing only the rhythms of his body-is the consummation of modern history. The rise of spacefaring man in modern history has seen the ascent of the free-floating individual, severed from sources of meaning, terrestrial astronauts adrift in urban bubbles and left to invent their own lives. Humanity itself comes to the end of the age listening like Ed White to the sound of its own breathing.

But if our severance from Earth is symbolic of this deepening isolation, it's also part of a communal awakening, a coming of age. The five-century quest for self-definition was founded on a repression of the feminine. But like the adolescent forging his own autonomy, we needed to go through that self-assertive masculine stage in order to reunite with the feminine at a higher turn of the spiral and recover our connection with the whole. A milestone in this process was the image of our fragile, lonely world rising over the dead moon, encouraging a rebalance from outer toward inner space, the self-awareness that comes when we realize that the parent is finite and mortal. If the age of exploration is the collective parallel to the growth of individual ego-consciousness, the astronaut's severance from the source is the final inflated act. From his literal alienation, his pilgrimage into the desert, comes communion with a larger reality. Seeing Earth not as an extension of man, but man as an extension of Earth, we come of age in the cosmos.

The dream of spaceflight seems to be a counterbalance at each phase of the cycle. The horizontal expansion of modern materialism has had as its counterpoint a longing for meaning, a vertical vision that seeks the whole over the part, the why over the how, meaningful ends over endless means. The pioneers of spaceflight, from Kepler to von Braun, have carried this quest for meaning across the modern desert. In the current transformation, however, it's the task of space advocates not only to awaken the vertical vision but to restore the risk-taking horizontal spirit to a self-immolating society.

8. You've predicted that the moon landing will be seen a thousand years hence as the signature of the twentieth century. Was it really any more significant than the airplane, television, nuclear weapons, or the computer?

A. It's not that other technologies have less pracical significance, but they tend to be increasingly extraordinary means to ever more ordinary ends, enhancing routine survival or providing analgesic distractions from the monotonous tension that the same technologies have created. There are many obvious exceptions-the accessibility of good music and the rare great film, and of course the means to information that expands our understanding of the human condition. But confined to one shrinking planet, even these things can take on a postmodern tinge, a kind of collective solipsism.

The ability to annihilate our entire species would seem at least equal in significance to spaceflight, which is simply its polar opposite. ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

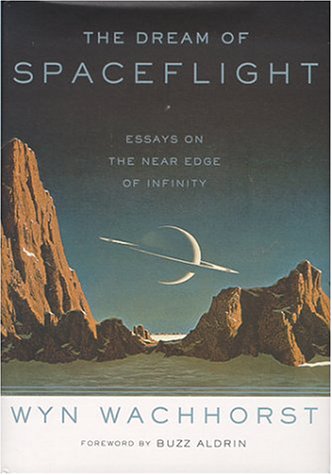

- PublisherBasic Books

- Publication date2000

- ISBN 10 0465090575

- ISBN 13 9780465090570

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages256

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Dream Of Spaceflight Essays On The Near Edge Of Infinity

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 4JSHAO004DIE

The Dream Of Spaceflight Essays On The Near Edge Of Infinity

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.85. Seller Inventory # 0465090575-2-1

The Dream Of Spaceflight Essays On The Near Edge Of Infinity

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.85. Seller Inventory # 353-0465090575-new

The Dream Of Spaceflight Essays On The Near Edge Of Infinity

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks164096

THE DREAM OF SPACEFLIGHT ESSAYS

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.85. Seller Inventory # Q-0465090575

THE DREAM OF SPACEFLIGHT ESSAYS

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.85. Seller Inventory # Q-9780465090570