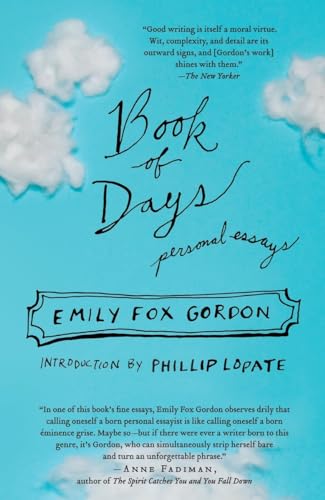

Items related to Book of Days: Personal Essays

Whatever the subject, Emily Fox Gordon’s disarmingly personal essays are an art form unto themselves—reflecting and revealing, like mirrors in a maze, the seemingly endless ways a woman can lose herself in the modern world. With piercing humor and merciless precision, Gordon zigzags her way through “the unevolved paradise” of academia, with its dying breeds of bohemians, adulterers, and flirts, then stumbles through the perils and pleasures of psychotherapy, hoping to find a narrative for her life. Along the way, she encounters textbook feminists, partying philosophers, perfectionist moms, and an unlikely kinship with Kafka—in a brilliant collection of essays that challenge our sacred institutions, defy our expectations, and define our lives.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Emily Fox Gordon is an award-winning essayist and the author of the novel It will Come to Me, and two memoirs, Mockingbird Years: A Life In and Out of Therapy and Are you Happy?: A Childhood Remembered. Her work had appeared in American Scholar, Time, Pushcart Prize Anthology XXIII and XXIX, the New York Times Book Review, Boulevard, and Salmagundi. She lives in Houston.

The photograph is small, printed on shiny black stock, black and white and curled at the edges. It represents me, at age two, sitting in the lap of what we called Library Hill, my arm loosely slung around the neck of our German Shepherd. His big head is cast upward as he tolerates my embrace, and his tongue lolls rakishly. We sit in a dent in the long grass. The wind has unsettled my tam o'shanter; the shoulder button of my overalls has come undone. My dog and I look happy, and a little idiotic.

Photographs like this are marked by the pathos and authority of a different time. In another, my mother poses with me and my infant brother, standing in front of our boxy Plymouth station wagon, grayish white in the picture but in historical fact a pale aquamarine. The year is 1949. She is wearing a mouton coat and heavy shoes with ankle straps. Her hair looks frizzy--she had probably just home-permed it--and her face is tired and pretty and young. My brother is a faceless bundle in the crook of her arm. Enough time has passed, enough of destiny has been realized for all three people in this picture so that looking at it gives me a little shock. It's as if I'd been waiting for a chronically turbulent pool of water to clear and, as a reward for my patience, had seen at the bottom a small brightly colored stone. We lived in two houses, one after the other, both rented from the college for, if I recall correctly, $125 a month. The houses sat next door to each other in a gentle declivity on a small meandering street next to the library and across from a freshman dormitory and the small white clapboard building which housed my father's department. In both houses we children felt the influence of the undergraduates, their beer parties and the shouts of their impromptu lacrosse games, from one direction, and the emanations of the alumni at the Williams Inn from the other, their chuckles and hoots over martinis in the lounge. Williams is a very old school; its campus is uncloistered, mixed with the town. At least it was then. Now both of my childhood houses are coeducational dorms.

The first house was low-slung and rambling and painted gray. After my family moved next door it housed the chairman of the Williams drama department and his dramatically bohemian wife. Wild parties spilled out onto the lawn and were gossiped about. Thornton Wilder, there for the Williams Theatre's production of Our Town, woke us up one early morning when he stumbled about on our lawn drunkenly, calling "Here, kitty, kitty, kitty." Still later, when scouts went looking for a quintessentially academic setting for the movie Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? that house, I'm told, was nearly chosen.

The other house was larger, a white Victorian wedding cake with tent-shaped attic rooms and a butler's pantry. A great chestnut tree grew in our yard, and every fall my brother and I gathered fallen pods, slit open the moist spiky green jackets and popped out the glossy inner nuts. We kept them in sacks and dragged them along to football rallies, threw the nuts into the bonfire for the pleasure of hearing them hiss and explode.

My memories of the first house are internal, centered on the furniture, the corners, the dark-yellow hopsacking curtains that turned morning sunlight butterscotch as it entered the room, the odd wallpaper in the dining room, diamond-shaped broken-line enclosures containing red-combed roosters. I remember moving my three-year-old hands along that cool wall, mumbling "A rooster, a rooster, a rooster," until I ran out of roosters. When my own daughter was the same age it occurred to me that another child might have counted the roosters. For me it was enough to repeat the name, over and over.

The second house I remember more for the views out of its windows. One of those stretches diaphanously across my mind's eye while I process grocery lists and weekly plans, like the faint background wash of flowery fields running under "Pay to the order of------" on the more expensive variety of personal checks. It's not a particularly interesting scene, just an uncropped view of the slanted roof outside my bedroom window, and the portico and green awning of the Williams Inn (a "Treadway Inn"). I also remember, but not so persistently and eidetically, a view from a later period, when I was allowed to move into one of the attic rooms. From there, high up, I could see College Place snaking along around the library. I could read the inscriptions carved in a marble scroll that ran below its roof--Ovid, Horace, Euclid, Plato. I could see the elms, which even then were moribund and leafless, sketchy goblets filled with air. The wind that shook the healthy, foliated trees left them unmoved.

In my early childhood my mother was a significant blur to me. I have trouble remembering her face when it was youthful, and I've had to piece together the person she was. Multitalented--indifferent to music but a competent pianist, a prolific seamstress, a watercolorist and cartoonist, a brilliant cook, a wit, a teacher with advanced pedogogical notions, an unrealized writer with perfect literary pitch and a deep love of the language, a sort of aesthetic heroine, a Renaissance woman. It seemed to me that my mother could do anything. Now it seems to me that my mother was trapped in an odd paralysis because she was so good at so many things. As she perfected her skills they became smoother and smaller; they became miniature.

There were other types of faculty wife, of course. A few were seriously but ineffectually intellectual, taking multiple advanced degrees, doing translations. More were musical. Others were odd, with a predilection for solitary pond-wading and insect collecting. What united them was a pride in accomplishment for its own sake, unremunerated and often unrecognized. My mother, I felt, was the queen of faculty wives.

Faculty wives still exist. I have turned out to be one, if only by default. These women staff the charity thrift shops, sell potted mums for the school benefit, hold season tickets for the symphony. At every potluck supper I attend, I can find them in the kitchen dressing salads and finding room in the oven for all the casseroles to warm. They are mostly middle-aged, but occasionally some shy young pregnant wife, who knows that her husband's professional future is so uncertain that when the baby comes she may be living in Salt Lake City, will find a harbor with them. These women seem grayer, chattier, more self-effacing every time I see them. They cluster together and make their own society, while out in the living room the female academics circulate freely among their male counterparts. There is a tension between these two varieties of women, and extended conversations between them are rare. Sometimes it happens that a female academic will arrive at one of these parties with a new baby, and she will bring it, as if in a ritual of obeisance, into the kitchen where the faculty wives will surround it, to coo and praise.

Once my mother had a bad dream which kept her quiet and low all day: our German Shepherd, whom she loved like a fourth child, had shrunk to the size of a bird, and been caged. She was subject to depression. I remember her in her sewing room, a length of periwinkle-blue corduroy draped across her lap, her mouth full of pins and her eyes full of tears. She had unexplained, and to me inexplicable, idle days, when she sat at the desk in the hall musing and doodling, drawing women's fingernails, perfectly oval, with delicately shaded quarter-moon cuticles.

My father was a big, fresh-faced man, balding from his early thirties. He grew up in Philadelphia, where his parents ran a corset shop. He and his younger brother lived in a household where several nephews were boarded; one of my cousins told me that the place had the feeling of a boys' dormitory. My grandparents lost all in the depression, recouped, lost money again because my grandfather--a savant who could do inventory in his head--had a weakness for the horses. Consequently, my father was tense about money all his life.

My father had the mark of brilliance on him and he shot up through the academic ranks of an emerging meritocracy fast; Phi Beta Kappa, editor of the newspaper at Swarthmore, Rhodes Scholar in economics. He had, I've been told, the "coup d'oeil," an ability to see the whole panorama of an abstract landscape at once. His studies at Oxford were interrupted by the war, and he returned to be drafted and serve behind a desk in Washington, D.C., where my older sister was born. Then he was recruited by Williams, and later on the Ford Foundation, and almost immediately after that the Kennedy administration. Things happened so fast to my father that he never got around to completing his Ph.D., and he was so busy thinking--he would often sit at the dinner table in a kind of cataleptic trance, his eyes wide and blank, his jaw hanging--that he never produced a book. Today, with these deficiencies, my father would never be able to get tenure at any university. Forty years ago, the academic world was roomier, yet to be regulated. But even then, I believe, my father felt himself to be out of place in academic life. He had an itch for action, an impatience with circumlocution, a blunt and colorful sense of humor. H. L. Mencken was his favorite writer, and his own style, in the few articles he wrote, was a model of balance and economy. He was admired by his students, who stood up to applaud him at the end of every semester, and he made many friends among the economists and their kinsmen, the political scientists. Many of these people sat over the remnants of my mother's very good dinners, talking for hours about things I found mystifying. I paid attention to tone, though, like an intelligent dog, and I always pricked up my ears for gossip and judgments. "Unsound," my father would say of somebody unknown to me, "bright but unsound," or "abysmal, just abysmal."

My father, who has now been dead for fifteen years, was a disastrous parent, worse than he deserved to be. He was deficient in self-knowledge and easily angered. When he turned to his children he seemed unable to modulate the hearty cynicism with which he looked at the world. "Who is Jack Frost?" I asked at the breakfast table. "Friend of your mother's," he answered, and smirked into his coffee cup. He could also be cruel: when I fell down the stairs at age five he stood over me for what seemed like a full minute, his expression disgusted. "I don't know whether to laugh or cry at you, Emily," he said finally, and walked away. He was mostly preoccupied, but he had some crudely behaviorist notions about child-rearing, which I got the worst of because I was so clumsy and absentminded. When I left the soap on the edge of the sink instead of in the soap dish, he would stand over me and make me replace it properly, remove and replace it again fifty times. And the same corrective was applied to all my other lapses: leaving the top off the toothpaste tube, forgetting to turn off lights, scratching the paint on the car when I parked my bike in the garage. "Careless" was his word for me. His provisions for reward were equally crude; after a good day he would usher me into his study and give me a quarter. My brother and sister were shrewd and strategic about my father; they anticipated his reactions and dodged his wrath. I continued all through my childhood to do all the things that infuriated him, and he continued using negative reinforcement in an effort to train me. Stupidly, bullheadedly, my father and I kept at it until at ten or eleven I conceded and retreated. I got back at him later, when adolescence gave me a new head of steam. At seventeen, when I had come home late and drunk from a party and he met me scowling at the door, I ran up all five flights of our Washington townhouse shrieking with laughter, flicking off lights as I went, leaving him--he already had a heart condition--in the dark. And in the late sixties, when my sister's Machiavellian boyfriend and I arranged a Christmas Eve insurrection, a drama of confrontation at my mother's festive dinner table, I let him have it. The boyfriend and I blamed him for everything--my mother's alcoholism, which by then was full-blown; the Vietnam War, which he abetted by supporting; the general unhappiness of our family. We left him in tears, and hugged each other in triumph while my mother and brother and sister looked on in dismay.

Sometimes, rarely, my father was kind. When a bad hot dog at a picnic made me sick, he put his hands on my heaving shoulders. He called me pet names--Um and Umbly--always full of implicit insult, but affectionate. I shuddered, and still shudder, with ambivalence about those names.

But I feel a solidarity with my father, perhaps because I look like him, bigger and heavier than the others in my family, with his long face and heavy eyebrows. Only my incongruously retrousse nose tells of my mother. And like him I'm chronically angry and love food more than I should, and insight has come hard and late for me.

My mother was magical. She floated birthday candles anchored in halved walnut shells in the tub when my brother and I were bathed. She turned off the light, lit the candles, and stood smoking a cigarette in a shadowy corner of the bathroom as we sat in the midst of a small shining armada.

my father's background was Jewish, my mother's Presbyterian. Both of them were agnostic rationalists, and I grew up hearing almost nothing of belief or doctrine. My mother preserved the aesthetic parts of her Christian heritage. We spent two weeks before Christmas, my mother, sister, brother, and I, at the kitchen table mixing food coloring into vanilla icing in small glass dishes--pale green, pink, a shade I called chocolate blue. We used toothpicks to paint striped frosting trousers on the rudimentary legs of gingerbread men, buttoned up their blurred pastel waistcoats with silvery sugar balls. We also collected pine cones and sprayed them, over newspaper, with silver and gold (the wonderful toxic reek of those spray cans, which were also preternaturally cold to the touch!); we saved the tops and bottoms of tin cans and used metal shears to cut them into stars and spirals for the Christmas tree.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRandom House

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 0385525893

- ISBN 13 9780385525893

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages320

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.50

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Book of Days: Personal Essays

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0385525893

Book of Days: Personal Essays

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0385525893

Book of Days: Personal Essays

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0385525893

Book of Days: Personal Essays

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0385525893

Book of Days: Personal Essays Gordon, Emily Fox and Lopate, Phillip

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.5. Seller Inventory # Q-0385525893

Book of Days: Personal Essays

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0385525893