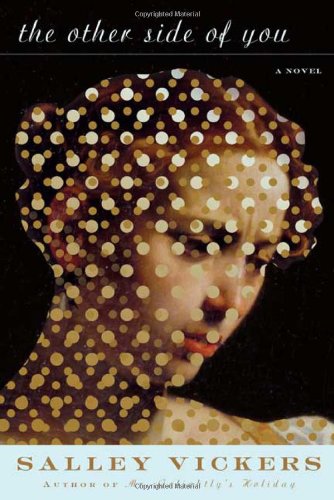

Items related to The Other Side of You: A Novel

For psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Dr. David McBride, death exerts an unusual draw. Despite his profession, he has never come to terms with the violent accident that took his brother’s life, a trauma that has shaped his personality and subsequent choice of career. But when a failed suicide, Elizabeth Cruikshank, comes into his care, he finds the deepest reaches of his suppressed history being reactivated. Elizabeth is mysteriously reticent about her own past and it is not until David recalls a painting by the Italian artist Caravaggio that she finally yields her story. As she recounts the chance encounter which took her to Rome, and her tragic tale of passion and betrayal, David begins to find a strange and disturbing reflection of his own loss in the haunted “other side” of this elusive woman. Through one long night’s dialogue they journey together into a past which brings painful new insight and uncertain resolution to each of them. The Other Side of You is a powerful meditation on art, and on love in all its manifestations. In distinctive, graceful prose, Salley Vickers explores the ways both love and art can penetrate the complexities of the human heart, to invade and change our being, and the possibilities of regeneration through another’s vision and understanding.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

A former psychologist and professor of English, Salley Vickers is the author of Miss Garnet's Angel, Instances of the Number 3 (FSG, 2002), and Mr. Golightly’s Holiday (FSG, 2004). She lives in London.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Chapter One

She was a slight woman, pale, with two wings of dark hair which framed her face and gave it the faintly bird-like quality that characterised her person. Even at this distance of time, which has clarified much that was obscure to me, I find her essence hard to capture. She was youthful in appearance but there was also an air of something ambiguous about her which was both intriguing and daunting. When we met she must have been in her forties, but in a certain light she could have been fourteen or four hundred – though when I say ‘light’ I perhaps mean that subtle light of the mind, which casts as many shadows as it illuminates but in the right conditions can reveal a person’s being more accurately than the most powerful beam. Once I would have known her age to the day, since it would have been part of the bald list of information on her medical file: name, sex, date of birth. Of the last detail I have a hazy recollection that her birthday was in September. She spoke of it once in connection with the commencement of the school year and a feeling that, in the coincidence of the month of her birth and a new term, she might begin some new life. ‘You see, Doctor,’ – when she used my title she did so in a tone that located it at a fine point between irony and intimacy – ‘even as a child I must have been looking for a fresh start.’ Doctors are like parents: there should be no favourites. But doctors and parents are human beings first and it is impossible to escape altogether the very human fact that certain people count. Of course everyone must, or should, count. We oughtn’t do what we do if that isn’t a fundamental of our instincts as well as of our professional dealings. But the peculiar spark that directs us towards our profession will have its own particular shape. I have had colleagues who come alive at a certain kind of raving, who perceive in the voices of the incurable schizophrenic a cryptic language, a Linear B, awaiting their special aptitude for decoding. One of my formidably brilliant colleagues has spent her life attempting to unravel the twisted minds of the criminally insane. It’s my opinion no one could ever disentangle that knot of evil and sickness, but for her it is the grail that infuses her work with the ardour of a mythic quest. My colleague Dan Buirski had a bee in his bonnet about eating disorders. I used to kid him, a long cadaver of a man himself, that he liked nothing more than a starving young woman to get his teeth into. I said once, ‘You’re no example, you’re a mere cheese paring yourself,’ and he laughed and said, ‘That’s why I understand them.’ He’s lucky with his metabolism, but his grandmother and his two uncles died in Treblinka. Starvation is in his blood and he’s converted that inheritance into a consuming interest in humankind’s relationship with food. It’s a strange business, ours. And what was my peculiar bent, the glimmer in my eye which has in it the capacity to lead me into dangerous swamps and mires? For me it was the denizens of that hinterland where life and death are sister and brother, the suicidally disposed, who beckoned. Like is drawn to like. Alter the biographical circumstances a fraction and my colleague who worked with psychopaths would make an expert serial killer: she had just the right streak of fanatical perfectionism and the necessary pane of ice in the heart. And for all his badinage, Dan had a hard time keeping a scrap of flesh on him. I saw him once, after he’d had a bad bout of flu, and I nearly crossed myself he looked so like a vampire’s victim. But despite the concentration camps, death wasn’t his particular lure. That was my province. It was a landscape I knew with that innate sense which people call ‘sixth,’ with the invisible antennae that register the impalpable as no less real than a kick in the solar plexus from a startled horse. To some of us it can be more real. It is said that the dead tell no tales, but I wonder. When I was five, my brother, Jonathan, was killed by an articulated lorry. It was my third day of school and our mother was unwell; and because our school was close by, and my brother was advanced for his six and a half years, and was used to going to and from school alone, she allowed him to take me there unescorted. The one road we had to cross was a minor one, but the lorry driver had mistaken his way and was backing round the corner as a preliminary to turning round. Jonny had stepped off the pavement and had his back to the lorry to beckon me across. Although he was mature for his age he was small, too small to figure in the mirror’s sight lines. I was on the pavement and I watched him vanish under the reversing lorry and I seem to remember – though this could be the construction of hindsight – that it was not until the vehicle started forward that I heard a thin, high scream, the sound I imagine a rabbit might make as a trap springs fatally on fragile bones. I doubt there was a bone left unbroken in my brother’s body when the lorry drove off, leaving the mess of shattered limbs and blood and skin which had been Jonny. I believe I saw what was left of him, before I was whirled away in the big, freckled arms of Mrs Whelan, who lived across the street and had heard the scream and rushed me into her house, which Jonny and I had never liked because it smelled of dismally cooked food, and terrified me by falling on her knees and dragging me down with a confused screech, ‘Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, the blessed lamb, may he rest in peace.’ Afterwards, I didn’t know where my brother was, but I was pretty sure it wasn’t with Jesus, Mary, or Joseph. The belief I clung to was that Jonny was still in the pine tree he had assured me was ‘magic,’ on whose stately curving boughs we used to swing together in Chiswick Park. I heard him more than once, when I was allowed back to play there. He was singing ‘He’ll be coming round the mountain when he comes,’ which was the song our mother sang when we were fretful, the two of us, on long car journeys. Later, when Mother had my twin sisters, born one behind the other within the hour, she sang other songs to them. From that time onwards, it was always ‘the girls’ and ‘Davey.’ I, Davey, was the wrong side of the unbridgeable fissure that had opened up in our family, and although I’m sure my parents loved me, I was a reminder of that small bloody mess they’d left behind. The lorry driver never recovered and had to be pensioned off, unfit for work. But my mother was made of sterner stuff. She had in her a fund of life that was not to be defeated even by life’s only real enemy. She was not a woman who lived on easy terms with her emotions. She was the daughter of a judge, and her upbringing, though liberal, had not bred in her a place for the easy expression of the finer shades of feeling. And I knew, too, though nothing in her outward demeanour ever gave this away, that if she could have chosen which son she had to lose, it would not have been Jonny. I didn’t blame her. After that, I was never going to be right for her again. I was the living witness to a calamity, the deeper reaches of which she could not afford to acknowledge if she was to continue to hold herself, and our family, together. Very likely she blamed me for the catastrophe. Why wouldn’t she? I blamed myself for it. My mother, for my father’s sake, for them to go on together, and for the family to survive, had to set her shoulders and turn her back on the disaster. She faced a choice, and she made it by abandoning me and jumping the ravine which had opened with Jonny’s death to the other side. It was a leap to the side of life, and the proof of this came in the form of my twin sisters, apples of my father’s eye and each other’s best companion. For a long time I was expecting my lost brother to come round that mountain, with all the confidence with which he had stepped off the kerb of the pavement and into the lorry’s fatal path. He was my closest companion, my hero, my single most important attachment to life. And when he didn’t come, and I heard only the echo of his voice in my ear, as I swung alone on the low pine branch, pretending, for my mother’s sake, that I was enjoying myself, a part of me wanted to go after him, for company.

Chapter Two

At the time I am speaking of I worked in two psychiatric hospitals in the south of England: a big red-brick, mock-Gothic pile in Haywards Heath, and a cosier, less oppressive place near Brighton on the south coast. In addition, I had a small private practice, where occasionally I saw some paying patients. From her appearance Mrs Cruikshank might have been one of those. She had the voice and mannerisms of someone born middle class. But I came to learn that this was part of a well-crafted veneer – like a piece of good furniture, she had a discreet sheen which was far from ordinary. In fact, she was the child of two immigrants, her father an Italian communist, who had come to England before the war; her mother, a refugee from the pre-revolutionary Yugoslavia, the illegitimate daughter of one of those two-a-penny Eastern European counts, or so she claimed. When I got to know her better, my patient told me she thought this may have been a compensating fantasy for the fact that her mother worked for a time as a dinner lady in the local primary school, the one her own daughter attended. Possibly the idea had conferred on the child a tincture of the aristocratic. Fantasies, if they are convinced enough, are also an element in the reality which shapes us, and there was a tilt to my patient’s narrow nose which might have given an impression of looking down it.

She was a slight woman, pale, with two wings of dark hair which framed her face and gave it the faintly bird-like quality that characterised her person. Even at this distance of time, which has clarified much that was obscure to me, I find her essence hard to capture. She was youthful in appearance but there was also an air of something ambiguous about her which was both intriguing and daunting. When we met she must have been in her forties, but in a certain light she could have been fourteen or four hundred – though when I say ‘light’ I perhaps mean that subtle light of the mind, which casts as many shadows as it illuminates but in the right conditions can reveal a person’s being more accurately than the most powerful beam. Once I would have known her age to the day, since it would have been part of the bald list of information on her medical file: name, sex, date of birth. Of the last detail I have a hazy recollection that her birthday was in September. She spoke of it once in connection with the commencement of the school year and a feeling that, in the coincidence of the month of her birth and a new term, she might begin some new life. ‘You see, Doctor,’ – when she used my title she did so in a tone that located it at a fine point between irony and intimacy – ‘even as a child I must have been looking for a fresh start.’ Doctors are like parents: there should be no favourites. But doctors and parents are human beings first and it is impossible to escape altogether the very human fact that certain people count. Of course everyone must, or should, count. We oughtn’t do what we do if that isn’t a fundamental of our instincts as well as of our professional dealings. But the peculiar spark that directs us towards our profession will have its own particular shape. I have had colleagues who come alive at a certain kind of raving, who perceive in the voices of the incurable schizophrenic a cryptic language, a Linear B, awaiting their special aptitude for decoding. One of my formidably brilliant colleagues has spent her life attempting to unravel the twisted minds of the criminally insane. It’s my opinion no one could ever disentangle that knot of evil and sickness, but for her it is the grail that infuses her work with the ardour of a mythic quest. My colleague Dan Buirski had a bee in his bonnet about eating disorders. I used to kid him, a long cadaver of a man himself, that he liked nothing more than a starving young woman to get his teeth into. I said once, ‘You’re no example, you’re a mere cheese paring yourself,’ and he laughed and said, ‘That’s why I understand them.’ He’s lucky with his metabolism, but his grandmother and his two uncles died in Treblinka. Starvation is in his blood and he’s converted that inheritance into a consuming interest in humankind’s relationship with food. It’s a strange business, ours. And what was my peculiar bent, the glimmer in my eye which has in it the capacity to lead me into dangerous swamps and mires? For me it was the denizens of that hinterland where life and death are sister and brother, the suicidally disposed, who beckoned. Like is drawn to like. Alter the biographical circumstances a fraction and my colleague who worked with psychopaths would make an expert serial killer: she had just the right streak of fanatical perfectionism and the necessary pane of ice in the heart. And for all his badinage, Dan had a hard time keeping a scrap of flesh on him. I saw him once, after he’d had a bad bout of flu, and I nearly crossed myself he looked so like a vampire’s victim. But despite the concentration camps, death wasn’t his particular lure. That was my province. It was a landscape I knew with that innate sense which people call ‘sixth,’ with the invisible antennae that register the impalpable as no less real than a kick in the solar plexus from a startled horse. To some of us it can be more real. It is said that the dead tell no tales, but I wonder. When I was five, my brother, Jonathan, was killed by an articulated lorry. It was my third day of school and our mother was unwell; and because our school was close by, and my brother was advanced for his six and a half years, and was used to going to and from school alone, she allowed him to take me there unescorted. The one road we had to cross was a minor one, but the lorry driver had mistaken his way and was backing round the corner as a preliminary to turning round. Jonny had stepped off the pavement and had his back to the lorry to beckon me across. Although he was mature for his age he was small, too small to figure in the mirror’s sight lines. I was on the pavement and I watched him vanish under the reversing lorry and I seem to remember – though this could be the construction of hindsight – that it was not until the vehicle started forward that I heard a thin, high scream, the sound I imagine a rabbit might make as a trap springs fatally on fragile bones. I doubt there was a bone left unbroken in my brother’s body when the lorry drove off, leaving the mess of shattered limbs and blood and skin which had been Jonny. I believe I saw what was left of him, before I was whirled away in the big, freckled arms of Mrs Whelan, who lived across the street and had heard the scream and rushed me into her house, which Jonny and I had never liked because it smelled of dismally cooked food, and terrified me by falling on her knees and dragging me down with a confused screech, ‘Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, the blessed lamb, may he rest in peace.’ Afterwards, I didn’t know where my brother was, but I was pretty sure it wasn’t with Jesus, Mary, or Joseph. The belief I clung to was that Jonny was still in the pine tree he had assured me was ‘magic,’ on whose stately curving boughs we used to swing together in Chiswick Park. I heard him more than once, when I was allowed back to play there. He was singing ‘He’ll be coming round the mountain when he comes,’ which was the song our mother sang when we were fretful, the two of us, on long car journeys. Later, when Mother had my twin sisters, born one behind the other within the hour, she sang other songs to them. From that time onwards, it was always ‘the girls’ and ‘Davey.’ I, Davey, was the wrong side of the unbridgeable fissure that had opened up in our family, and although I’m sure my parents loved me, I was a reminder of that small bloody mess they’d left behind. The lorry driver never recovered and had to be pensioned off, unfit for work. But my mother was made of sterner stuff. She had in her a fund of life that was not to be defeated even by life’s only real enemy. She was not a woman who lived on easy terms with her emotions. She was the daughter of a judge, and her upbringing, though liberal, had not bred in her a place for the easy expression of the finer shades of feeling. And I knew, too, though nothing in her outward demeanour ever gave this away, that if she could have chosen which son she had to lose, it would not have been Jonny. I didn’t blame her. After that, I was never going to be right for her again. I was the living witness to a calamity, the deeper reaches of which she could not afford to acknowledge if she was to continue to hold herself, and our family, together. Very likely she blamed me for the catastrophe. Why wouldn’t she? I blamed myself for it. My mother, for my father’s sake, for them to go on together, and for the family to survive, had to set her shoulders and turn her back on the disaster. She faced a choice, and she made it by abandoning me and jumping the ravine which had opened with Jonny’s death to the other side. It was a leap to the side of life, and the proof of this came in the form of my twin sisters, apples of my father’s eye and each other’s best companion. For a long time I was expecting my lost brother to come round that mountain, with all the confidence with which he had stepped off the kerb of the pavement and into the lorry’s fatal path. He was my closest companion, my hero, my single most important attachment to life. And when he didn’t come, and I heard only the echo of his voice in my ear, as I swung alone on the low pine branch, pretending, for my mother’s sake, that I was enjoying myself, a part of me wanted to go after him, for company.

Chapter Two

At the time I am speaking of I worked in two psychiatric hospitals in the south of England: a big red-brick, mock-Gothic pile in Haywards Heath, and a cosier, less oppressive place near Brighton on the south coast. In addition, I had a small private practice, where occasionally I saw some paying patients. From her appearance Mrs Cruikshank might have been one of those. She had the voice and mannerisms of someone born middle class. But I came to learn that this was part of a well-crafted veneer – like a piece of good furniture, she had a discreet sheen which was far from ordinary. In fact, she was the child of two immigrants, her father an Italian communist, who had come to England before the war; her mother, a refugee from the pre-revolutionary Yugoslavia, the illegitimate daughter of one of those two-a-penny Eastern European counts, or so she claimed. When I got to know her better, my patient told me she thought this may have been a compensating fantasy for the fact that her mother worked for a time as a dinner lady in the local primary school, the one her own daughter attended. Possibly the idea had conferred on the child a tincture of the aristocratic. Fantasies, if they are convinced enough, are also an element in the reality which shapes us, and there was a tilt to my patient’s narrow nose which might have given an impression of looking down it.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFarrar, Straus and Giroux

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0374221901

- ISBN 13 9780374221904

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 59.00

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Other Side of You: A Novel

Published by

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0374221901

ISBN 13: 9780374221904

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks63816

Buy New

US$ 59.00

Convert currency

The Other Side of You

Published by

Farrar Straus & Giroux

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0374221901

ISBN 13: 9780374221904

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 262 pages. 8.50x6.00x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0374221901

Buy New

US$ 50.59

Convert currency

THE OTHER SIDE OF YOU: A NOVEL

Published by

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0374221901

ISBN 13: 9780374221904

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.9. Seller Inventory # Q-0374221901

Buy New

US$ 74.52

Convert currency